The Highland Light (previously known as Cape Cod Light), an active lighthouse on the Cape Cod National Seashore in North Truro, Massachusetts, on the Outer Cape Code, is the oldest and tallest lighthouse on Cape Cod, and the 20th lighthouse built in the USA. It is owned by the National Park Service (a Cape Cod National Seashore property) and cared for by the Highland Museum and Lighthouse, Inc., while the United States Coast Guard operates the light itself. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as Highland Light Station.

In 1700, the town of Truro, Massachusetts, nine miles east of Race Point at the tip of Cape Cod, began its history under a different name—one it easily earned: “Dangerfield.” Even in calm weather, fishermen could suddenly find upon approaching land such a swell breaking that they dared not attempt to come ashore.

“I found that it would not do to speak of shipwrecks in the area, for almost every family had lost someone at sea,” Henry David Thoreau would later write about Truro in the December 1864 issue of Atlantic Monthly. “‘Who lives in that house?’ I inquired. ‘Three widows,’ was the reply. The stranger and the inhabitant view the shore with very different eyes. The former may have come to see and admire the ocean in a storm; but the latter looks on it as the scene where his nearest relatives were wrecked.”

Blindingly dense summer fogs lasting till midday that turn (in Thoreau’s words) “one’s beard into a wet napkin about the throat” provide conditions that to this day challenge even the most experienced mariner. The letter Reverend James Freemen wrote petitioning for a lighthouse near Truro stated that in 1794 more vessels were wrecked on the east shore of Truro than in all of Cape Cod.

On May 17th 1796, President George Washington signed the bill, along with $8,000 budget, authorizing a wood lighthouse to warn ships about the dangerous coastline between Cape Ann and Nantucket. It was the first light on Cape Cod, situated on ten acres on the Highlands of North Truro, was usually the first light seen when approaching the entrance of Massachusetts Bay from Europe.

The nation’s first eclipser was installed in the lantern room to differentiate Highland Light from others on the way to Boston, but delays in receiving it pushed the inaugural illumination back to January 15, 1798. With a focal plane of 180 feet above the sea, the light, with its array of lamps and reflectors, had the potential to be seen up to twenty-four miles, but the haze that often hung over the cape reduced the light’s visibility. Sperm whale oil was initially used in the light, but the fuel was later changed to lard.

In 1833, the wood structure was replaced by brick and in 1840 a new lantern and lighting apparatus was installed. In 1857 the lighthouse was declared dangerous and demolished, and for a total cost of $17,000, the current 66 foot brick tower was constructed, with a first order Fresnel lens from Paris. Along with the lighthouse, there was a keeper’s building and a generator shed, both of which can still be seen today.

In 1854, $25,000 was budgeted to rebuild Cape Cod Lighthouse on a proper site and to fit it with the “best approved illuminating apparatus to serve as substitution for three lights at Nauset Beach.”

Construction did not begin until 1856 on a new sixty-six-foot tower and a dwelling for the head keeper and a double-dwelling for his two assistants. The lighthouse was completed in October 1857, for $17,000, which included a new first-order Fresnel lens that produced a fixed white light. Before the addition of the first-order lens, the station had employed just one keeper.

The sixty-nine winding steps leading to the lantern room could be quite tricky for man.

In 1873, $5,000 was allocated for the station to receive a first-class Daboll trumpet fog horn that gave blasts of eight seconds, with intervals between them of thirty seconds. A frame engine-house, measuring twelve feet by twenty-four feet, was built for the fog signal along with a fuel shed.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, duplicate four-horsepower oil engines with compressors replaced the old caloric engines, reducing the time needed to produce the first blast of the fog signal from forty-five to ten minutes. In 1929, an electrically operated air oscillator fog signal was installed at the station as mariners complained that the old reed horns could hardly be heard above the heavy surf crashing on the beach below the station. Power for operating the new signal was furnished by a direct-current generator, driven by a four-cycle, internal-combustion engine that ran on kerosene.

On June 6, 1900, Congress appropriated $15,000 for changing the light’s characteristic from fixed to flashing. The new Barbier, Benard & Turenne first-order Fresnel lens had four panels of 0.92 meter focal distance, revolved in mercury, and gave, every five seconds, flashes of about 192,000 candlepower nearly one-half second in duration. While the new lens was being installed, the light from a third-order lens was exhibited atop a temporary tower erected near the lighthouse. After the new light was exhibited on October 10, 1901, the temporary tower was sold at auction.

In 1946, the Fresnel lens was replaced with a Crouse-Hinds, double-drum, rotating DCB-36 aerobeacon, which was in turn replaced during the automation process in 1987 with a Crouse-Hinds DCB-224 rotating beacon. The Fresnel lens was mostly destroyed during its removal, but a piece is on display at the lighthouse.

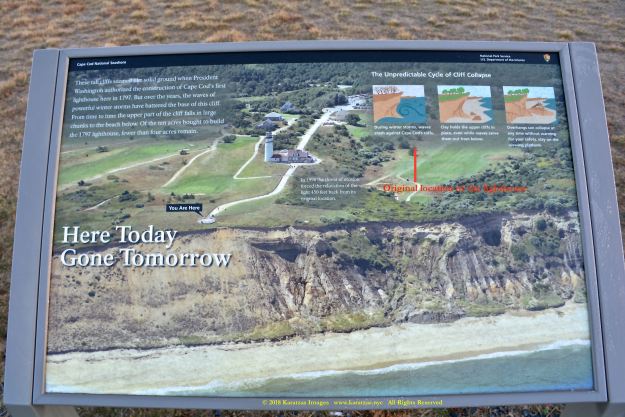

By the 1960s, the assistant keeper’s double-dwelling and fog horn building had been removed, and Keeper Isaac Small’s original ten acres had shrunk to little more than two. In the early 1990s, erosion seriously threatened the light. While in 1806, the tower had stood 510 feet from the cliff, by 1989, that distance had shrunk to just 128 feet.

Highland Lighthouse attracted visitors even when it was staffed by resident keepers. In 1922, 7,300 people registered at the lighthouse. Highland Museum and Lighthouse, Inc. was formed in 1998 as a non-profit to partner with the National Park Service in running a gift shop in the keeper’s dwelling and in offering tours of the lighthouse. After fifteen years in this role, the non-profit lost its contract due to operational issues, and on January 1, 2014, Eastern National was awarded the contract for operating the lighthouse.

The present location of the lighthouse is not the original site as beach erosion had rendered the original location dangerous. The structure was moved 450 feet (140 m) to the west from the cliff’s edge. The move was undertaken in 1996 at a cost of $1.5 million. The 430-ton structure was successfully moved intact on I-beams greased with Ivory soap.

Formerly a location associated with notable danger, the lighthouse presently is surrounded by an oceanfront golf course, the Highland Golf Course. After an errant golf ball broke a window, they were replaced with unbreakable material. The lighthouse grounds are open year-round on Highland Light Road in Truro, with tours and the museum available by the National Park Service during the summer months.

Highland Light Station is located on Highland Rd. in North Truro. Traveling north on Rte. 6, take the “Cape Cod/Highland Rd.” exit; turn right onto Highland Rd. and follow to the Highland Lighthouse area. Highland Light Station is situated on grounds owned by the National Park Service as part of the Cape Cod National Seashore and is managed by the Truro Historical Society. The grounds are open all year and the lighthouse is open May-October. A trip to the light station allows the visitor to enjoy the Interpretive Center, watch a 10-minute video and climb the lighthouse tower for a small fee. For further information, visit the Truro Historical Society‘s website or call 508-487-1121.

Sources:

Cape Cod (Highland), MA, LighhouseFriends.com

Maritime History of Massachusetts

Highland Light (Cape Cod Light) at dawn. Image credit: Karatzas Images

Image of Highland Light (Cape Cod Light) at dawn. Image credit: Karatzas Images

Image of Highland Light (Cape Cod Light) at dawn. Image credit: Karatzas Images

Image of Highland Light (Cape Cod Light) at dawn. Image credit: Karatzas Images

Image of Highland Light (Cape Cod Light) at dawn. Image credit: Karatzas Images

Image of Highland Light (Cape Cod Light) at dawn. Image credit: Karatzas Images

Image of Highland Light (Cape Cod Light) at dawn. Image credit: Karatzas Images

Visual depiction of the Highland Light (Cape Cod Light) with original and present location of the lighthouse indicated; cliff erosion is clearly visible. Image credit: Karatzas Images

Landmarks of the Highland Light (Cape Cod Light). Image credit: Karatzas Images

Image of Highland Light (Cape Cod Light) at dawn. Image credit: Karatzas Images

Image of Highland Light (Cape Cod Light) at dawn. Image credit: Karatzas Images

Image of Highland Light (Cape Cod Light) at dawn. Image credit: Karatzas Images

© 2013 – present Basil M Karatzas & Karatzas Images. All Rights Reserved.

IMPORTANT DISCLAIMERS: The purpose of this blog is for entertainment and information purposes. Vessel description(s), if any, is/are provided in good faith and believed to be correct and accurate but no assurances, warranties or representations are made herewith. Any vessel description(s) is/are provided for entertainment purposes only. We assume no responsibility whatsoever for any errors / omissions in vessel description.

Access to this blog signifies the reader’s irrevocable acceptance of this disclaimer. No part of this blog can be reproduced by any means and under any circumstances, whatsoever, in whole or in part, without proper attribution or the consent of the copyright and trademark holders of this website. To purchase rights or merchandise of high resolutions images and art presented here, please visit www.karatzas.nyc or email < info [at] BMKaratzas.com >. Thank you for the consideration.