Tall ships are the last few living objects of ages past, like hands with long arms protruding from the past to our times, like long piers coming to our life from the sea of another epoch to teach us how things and life used to be back then, to narrate us with the stories, the passions and the aspirations of our collective progenitors and the people who used to ‘man’ them and their women and societies waiting for them back at their homily hearth. Given that tall ships in many respects were the absolute epitome of their times in terms of man-made structures depending on cutthroat navigation, engineering and business enterprising that were meant to trade at the cultural intersections of a much smaller world on a much bigger globe then, with their sleek lines, their towering masts, their shapely hulls and their now unnecessary but highly romantic sails, it is no surprise that tall ships seem to always draw the attention of the touristic public. As ever, it is not cheap to maintain such vessels shipshape, but several governments and non-profit organizations have taken it upon themselves to selectively preserve some of these vessels in the name of history, national pride, education and maritime tradition.

The Swedish tall ship „Götheborg” will be our honored flagship in a series of postings on tall ships that still proudly crisscross the ocean in mostly educational and cultural missions these days, much to the delight of citizenry of visiting ports.

The modern day „Götheborg” got under planning and construction in 1994, ten years after the shipwreck of the original vessel was discovered in 1984. The construction period was long in the gestation since no plans of the original vessel were preserved and the organization for building the vessel, “The Swedish Ship Götheborg” organization (Ostindiefararen Götheborg), opted for traditional and historically accurately means of building the vessel rather than deploying modern methods of marine construction and engineering. The vessel was built at one of the four active shipyards in 18th century Stockholm Eriksberg yard at Terra Nova In Stockholm. Her construction cost (including marine archeological surveys and research) is estimated at more than $40 million, half of it procured by the Swedish government and the rest from individual donations and sponsorships.

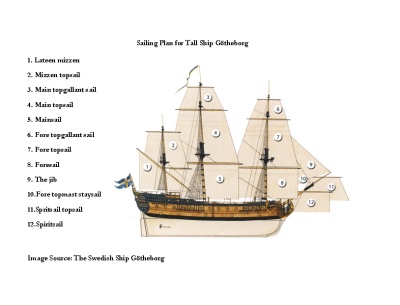

Götheborg’s Sailing Plan (Image source: The Swedish Ship Götheborg)

„Götheborg”, world’s largest operational wooden sailing vessel today, is a full-rigged, squared-sailed vessel with three masts and three decks and twenty cabins for a total crew of sixty; she has 26 sails, including the studdingsails, made of canvas, and 1,964 m2 total sail area. The mainmast and the foremast have topgallant sails, topsails and courses. The aftermast has a topsail and a Latin type spanker sail. In the bow is the bowsprit with a jib boom, and hanging below that are two more square sails: the spritsail and the sprit-topsail. The hull is 47 meters in length with 11-meter beam, 5.5 meters freeboard and 47 meters air draft. As a matter of comparison, Nelson’s man-of-war flagship HMS „Victory” launched in 1765 had a hull 57 meters length and about 5,500 m2 sail area.

More than 3,000 m2 of oak forest and one thousand oak logs had to be harvested from southern Sweden and Denmark to make the hull, and pine, spruce and elm were used for masts, jibs, spars, decks and blocks. The vessel is a faithful replica of the original East Indiamen with the exception that the lower and upper decks have 10 cm more headroom (sailing ships had their decks in short proximity that would not allow for people to walk upright). The vessel also has received the benefit of modern technology and several amenities in certain respects, such as two folding propellers and two 550 hp engines, power generator and power circuits, high-pressure sprinklers for fire safety, modern kitchen with fridges and freezers, water generators for producing drinking water, ventilation, air conditioning and a complete laundry room. Modern amenities are concealed within the ship creating ‘two ships in one’ and allowing for the vessel to be classed by DNV for ocean going navigation and keeping abreast with current maritime safety regulations.

Sweden was trading with China over terrain through the Silk Road still several decades after the other European powers (English, French, Dutch, Danish and Portuguese) had established their East India companies and had launched commercial fleets of imposing wooden sailing vessels (“East Indiamen”) to trade tea, silk, spices and porcelain, the hot commodities of the time, and make fortunes in the process. England in 1600 and the Netherlands in 1602 were the fist to establish their trading companies (East India Company and Dutch East India Company, respectively) for trading with the exotic Orient, while Sweden was last to the game in 1732 with the Swedish East India Company (Svenska Ostindiska Companiet, “SOIC”). Although small by European standards, the company was huge in Sweden at the time and had tremendous impact on the insular Swedish society; it is said that SOIC has been the most profitable company in Sweden ever. Between 1732 and 1813, the company undertook 132 expeditions with 38 ships, eight of which that were perished. Under the company’s royal charter, SOIC could employ as many vessels as needed, but all had to be built in Sweden, flying the Swedish flag and carrying Swedish documents; all expeditions had to originate from and terminate at the port of Gothenburg, where all imported goods were auctioned upon arrival; the state was receiving a flat fee per expedition form the company plus imposed percentage tax on the sales of the goodies. Although the company enjoyed secrecy for this roster of shareholders and its finances, it is believed than many voyages generated more than 60% return on invested capital – each voyage was a standalone project – and it’s said that several modern wealthy Swedish families derive their status and original wealth from the SOIC.

The first vessel of SOIC, the „Friedericus Rex Sueciae”, sailed from Gothenburg on 9 February 1732 and reached Canton (Guangzhou), the main port of China at the time, 181 days later; on her return voyage, she was arrested by the Dutch between Java and Sumatra, and was brought to Batavia (Dutch colonies in Indonesia) on suspicion of piracy (for a vessel flying the Swedish flag in the Pacific Ocean was not a common sight after all, but likely the Dutch were protecting their ‘franchise’, should we say), and eventually the vessel was released unharmed; the vessel reached the port of Gothenburg in late summer 1733, eighteen whole months after her commencing of the expedition; the first trip was very successful, even by today’s private equity standards, as it delivered 25% dividend on capital invested.

The original vessel „Götheborg” was built in Terra Nova in Gothenburg in 1738, six years after the royal charter of SOIC. She completed two successful uneventful round voyages to China. Her third voyage took thirty months to develop, including a five-month wait period in Java for the right winds to sail the vessel westerly, and finally, in September 1745 with her cargo holds laden to the beams with tea, silk, porcelain, tutanego (zinc), spices and much more, within sight of the coast and with pilot onboard, the „Götheborg” run aground on well charted rock Knipla Hunnebådan, around 900 metres west of Nya Älvsborgs Fästning, started taking water and finally sunk. Thankfully, there was no loss of life and some of the cargo was partially salvaged. Despite the loss of the vessel and most of the cargo, it’s said that her last voyage still generated 17% return for her investors.

The Swedish Underwater Archaeology Society’s Gothenburg group has undertaken several exploratory missions to the site of the shipwreck since 1984, and with most of the wreck buried in the seabed, extensive marine archaeological surveys took place every summer until 1992, to retrieve sizeable pieces of her hull, cargo and crucial information to build a faithful replica of the vessel. It took almost ten year from keel laying to completing the modern copy, always using traditional shipwright means, and her launching took place on Sweden’s National Day on June 3rd 2003 in the presence of the Swedish Royal Family. The maiden voyage of the vessel in October 2005 could only have one destination (China!) after calling ports of the original route in Cadiz, Spain, Cape Town, South Africa and Jakarta, Indonesia. It is said that the state visit of Chinese president Hu Jintao to Stockholm in June 2007 was planned to coincide with the return of the vessel to Gothenburg from her maiden voyage to China.

„Götheborg” next expedition commences in March 2014 from Gothenburg with expected arrival to Quanzhou, China on October 1st, China’s National Day.

© 2013 Basil M Karatzas & Karatzas Marine Advisors & Co. All Rights Reserved.

IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER: Access to this blog signifies the reader’s irrevocable acceptance of this disclaimer. No part of this blog can be reproduced by any means and under any circumstances, whatsoever, in whole or in part, without proper attribution or the consent of the copyright and trademark holders of this website. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure that information herewithin has been received from sources believed to be reliable and such information is believed to be accurate at the time of publishing, no warranties or assurances whatsoever are made in reference to accuracy or completeness of said information, and no liability whatsoever will be accepted for taking or failing to take any action upon any information contained in any part of this website. Thank you for the consideration.

'

'